Accrington Football Club

While this site is dedicated to the current Accrington Stanley Football Club, re-formed in 1968, the town of Accrington itself boasts a rich and storied history in both League and Non-League football.

It’s a common misconception—often perpetuated by careless journalism and misleading online content—that Accrington Stanley were among the original founder members of the Football League. In reality, this isn’t the case. However, the town was indeed represented in that historic group of 12 founding clubs by Accrington FC, a separate and earlier team that helped shape the beginnings of professional football in England.

In the beginning

Accrington FC was born out of the town’s cricket club, whose members sought a suitable sport to occupy the winter months. The origins of the football club are believed to date back to 1876—around the same time the cricket club was playing at Peel Park. However, it wasn’t until a meeting held in 1878 at the Black Horse Public House on Abbey Street that the decision was made to adopt association football rules. Prior to this, matches had been played under a loose and uncompetitive blend of association and rugby codes.

The club’s distinctive colours of scarlet and black were chosen by then-president Colonel Hargreaves, earning the team the nickname “Th’Owd Reds.” Around this time, the cricket club had just relocated to its new headquarters at Thornleyholme Road, where Accrington FC played their first competitive fixture on 28th September 1878—a 2–1 victory over Church Rovers FC.

Still in its formative years, Accrington FC received a remarkable invitation to take part in one of the earliest floodlit football matches ever recorded. The game, held on 1st November 1878 at Alexandria Meadows—home of Blackburn Rovers—was billed as an “Exhibition of Electric Light.” While Blackburn ran out 3–1 winners, the result was of little consequence; the real spectacle was the pioneering use of artificial illumination.

Not to be outdone, Accrington staged their own floodlit fixture just two weeks later, hosting Church FC at Thornleyholme Road on 20th November. True to Accrington tradition, however, the event came with its fair share of mishaps. The steam engine required to power the lights—provided by Bury & Parker of Manchester—was damaged during transit at the railway station. In a last-minute rescue, the local gas company stepped in to provide a replacement.

The match itself began dramatically, with Church taking the lead in the first minute. Accrington equalised by the tenth, only for one of the two floodlights to fail immediately after. During the ensuing 30-minute delay, the players entertained the 3,000-strong crowd by kicking the ball around and playing leapfrog, while the Accrington Brass Band kept spirits high.

The match eventually ended in a 3–3 draw, but the floodlighting experiment was short-lived. The novelty faded across the country, and the idea was shelved for decades. Remarkably, it would be 76 years before floodlights returned to the town—when Accrington Stanley (1921), the spiritual successors to the original club, became one of the first in the country to install a permanent system.

By the end of their inaugural season, Accrington FC had played a total of 25 matches—winning 17, drawing 1, and losing just 7. This impressive record was considered a strong foundation for a newly formed club, and optimism was high as preparations for the following season were already underway.

Let’s get competitive

The 1879/80 season marked Accrington FC’s first foray into competitive cup football, as they entered the inaugural Lancashire Cup. Their opening fixture, a home tie against Halliwell of Bolton, was the club’s first official competitive match—and a successful one at that, with Accrington securing a 4–1 victory. Momentum continued in the second round with a 3–0 win over Blackburn St. Marks (formerly Witton St. Marks).

Accrington’s cup run gathered pace with a 4–1 triumph against Lower Darwen, followed by a hard-fought 4–3 victory over Lower Chapel. These wins earned them a semi-final showdown away at Blackburn Rovers on 6th March. Despite a spirited performance, the Reds were ultimately outmatched by the more established Blackburn side, who progressed to the final with a 3–1 win.

Undeterred, Accrington returned for the 1880/81 Lancashire Cup campaign with renewed determination—and this time went one step further. They began their journey with a 3–1 win over Astley Bridge, another Bolton-based club, followed by a comfortable 4–1 home victory against Padiham. A trip to Witton (formerly Blackburn St. Marks) in the next round ended in a resounding 6–2 win, setting up a home semi-final clash with Enfield, where Accrington cruised to a 3–0 victory.

With both Blackburn Rovers and Darwen expelled from the Lancashire Cup, Accrington entered the 1880/81 final as clear favourites to claim their first piece of silverware. The final, played on 23rd April at Darwen’s Barley Bank Ground, drew a crowd of over 4,000. In a thrilling encounter against Blackburn Park Road, Accrington emerged victorious with a 6–4 win—lifting the Lancashire Cup and securing their place in local footballing history.

The momentum continued into the 1881/82 season, as “Th’Owd Reds” entered the FA Cup for the first time. They were drawn at home against leading Scottish side Queen’s Park, but the match was never played—Queen’s Park, unable to raise sufficient funds for travel, withdrew, granting Accrington a walkover. In the second round, however, Accrington were defeated 3–1 away to Darwen.

Meanwhile, in the Lancashire Cup, Accrington embarked on another prolific run. They opened their campaign with a commanding 9–1 victory over Blackpool, followed by an 8–0 demolition of Rishton. A 5–0 away win at Halliwell led into a thrilling 7–3 triumph over Bolton Wanderers at home. The semi-final, once again held at Darwen’s Barley Bank Ground, saw Accrington edge out Witton 2–1—only for Witton’s protest over an alleged unregistered player to be upheld. In the replayed match, Accrington left no doubt, winning 4–2 to reach their third consecutive final.

The final took place at the Turf Moor Cricket Ground in Burnley and attracted over 5,000 spectators. Accrington faced Blackburn Rovers and were ultimately beaten 3–1 by the more dominant side. Yet the match was played under a cloud of growing controversy: the Lancashire FA had begun expressing concern over the use of ‘non-local’ players and the suspected practice of covert payments. The spectre of professionalism—still officially banned—was looming ever larger, and the issue would come to a head within just two years.

By the close of the 1881/82 season, Accrington’s fortunes looked promising on the pitch. Off it, however, trouble was brewing. The Cricket Club, which owned Thornleyholme Road, had permitted the construction of a seated grandstand along the football pitch. Yet just a year later, they insisted that the structure be dismantled after every match—a decision that marked the beginning of a strained and ultimately fractious relationship between the football club and its landlords.

1882/83: Local Rivals and Off-Field Disputes

By the 1882/83 season, Accrington FC was facing growing competition from a number of emerging clubs in and around the town, including Stanley Rovers, Peel Bank Rovers, Accrington Ramblers, and Accrington Remnants. Despite this increase in local activity, Accrington remained the premier team in the area, largely thanks to the higher calibre of players on their books.

In the FA Cup, however, Accrington made an early exit, falling 3–6 in the first round to Blackburn Olympic. Their Lancashire Cup campaign began more promisingly with a commanding 7–0 victory over Great Harwood, but hopes were dashed in the next round as they suffered a narrow 2–3 defeat to Blackburn Park Road.

Off the pitch, tensions with the club’s landlords—the Cricket Club—intensified. In April, the Cricket Club proposed a full amalgamation, suggesting the formation of a single entity: Accrington Cricket and Football Club. At a time when other clubs, such as Darwen, were moving toward independence from their cricketing counterparts, this suggestion felt like a step backward.

During a heated meeting held on 1st May 1883, the Football Club firmly opposed the proposal, citing their unwillingness to be subject to decisions made solely by the Cricket Club’s committee. The Cricket Club countered, reminding their tenants that they held the lease on the ground and had spent £350 on levelling and drainage—work that would not have been necessary for cricket alone. After a series of contentious exchanges at a subsequent Cricket Club meeting, a vote was held: the proposal was defeated by 21 votes to 13. While the status quo remained, the relationship between the two clubs was now visibly strained. The Cricket Club couldn’t afford to evict their tenants, and the Football Club couldn’t afford to relocate—leaving both locked in an uneasy stalemate.

The Scapegoats

By 1882, Accrington FC had come to a stark realisation: to compete with the region’s top clubs—most notably Darwen and Blackburn Rovers—they would need to significantly upgrade the quality of their playing squad. This ambition meant looking beyond the town’s borders, particularly to Scotland, where players had already begun to earn a reputation for their skill and tactical intelligence.

Darwen had pioneered the recruitment of Scottish players as early as 1878, and the practice was rapidly gaining traction across the industrial North. But while it was an open secret that these imports were being paid to play, the national Football Association—still rooted in the amateur ideals of the South—officially forbade professionalism.

Like many of their rivals, Accrington maintained the fiction that their Scottish recruits played solely for the love of the game. But it soon emerged that players were receiving as much as £5 per match. Although similar practices had been widespread for years, it was Accrington who found themselves cast as the scapegoats. In November 1884, the club was sensationally expelled from both the Football Association and the Lancashire FA, banned from all cup competitions and even friendly fixtures—a punishment that was partially relaxed not long after.

At the time of their expulsion, Accrington had already secured a 3–0 win over Southport Central in the FA Cup First Round, though they had withdrawn from the Lancashire Cup before the ruling was handed down.

The harsh treatment of Accrington sent ripples through the northern football community. In a remarkable show of solidarity, a number of other ‘professional’ clubs refused to confirm or deny whether they too were paying players. This act of defiance led to the bold proposal of a breakaway organisation—the British Football Association—as a counterweight to the increasingly out-of-touch, amateur-dominated FA.

Sensing the growing rebellion and the real threat of disintegration, the FA convened in 1885 to reconsider its stance. Under mounting pressure from the North, the Association finally relented. In July 1885, it was formally announced that professionalism would be legalised—players could now be paid for their services and still compete in official competitions.

With the ban lifted, clubs across England began signing Scottish players in droves. Accrington wasted no time. In December 1884 alone, four Scots joined their ranks: Bonnar and Conway from Thornliebank, McBeth from St. Bernard’s, and Stevenson from Arthurlie—ushering in a new era for the club, and for English football as a whole.

Professionalism in Accrington

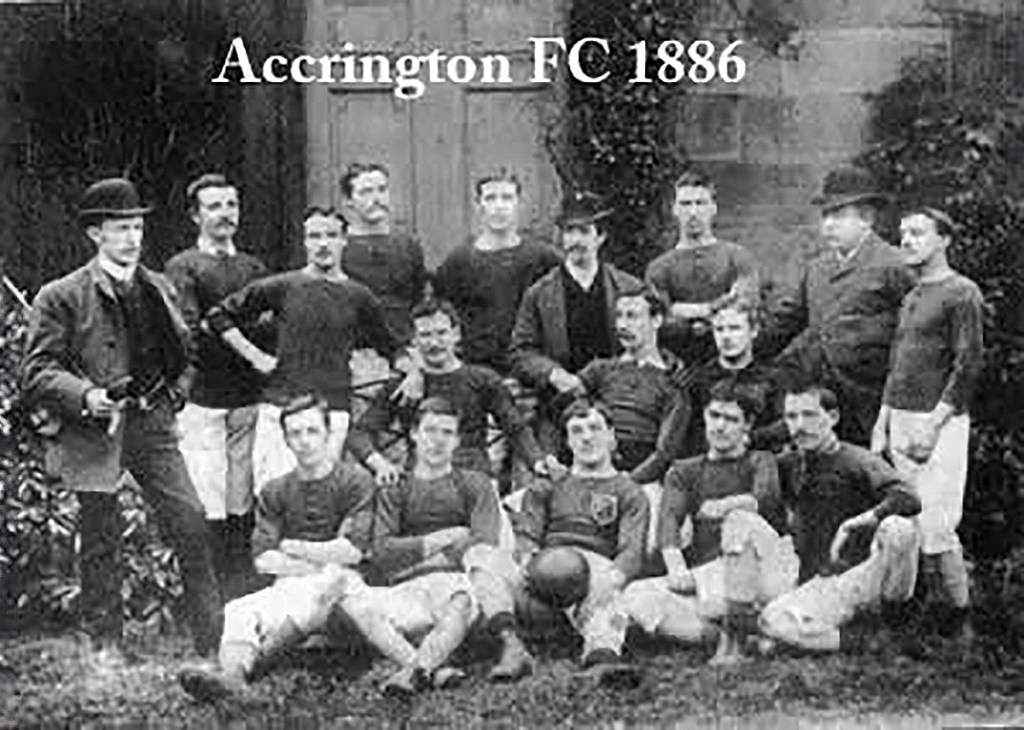

The 1885/86 season saw Accrington FC strengthen its ties with the Scottish game, arranging more fixtures north of the border with a clear eye on scouting potential talent. These matches were not only competitive tests but also an opportunity to lure skilled players south, now that professionalism had been officially sanctioned.

Among the visiting Scottish sides, St. Bernard’s were beaten 4–2 in a spirited home performance. However, sterner tests came in the form of Scottish Cup holders Dumbarton and Pollock Shields Athletic, with Accrington suffering a 4–0 defeat to the former and a narrow 2–1 loss to the latter.

In the FA Cup, the club faced local rivals Witton in a thrilling First Round home tie. In a goal-laden encounter, Accrington edged their visitors 5–4. The Second Round, however, brought disappointment, with a 1–2 defeat away to Darwen Wanderers cutting short their cup run.

The Lancashire Cup provided a similar pattern of hope and frustration. A hard-fought 2–1 away victory at Clitheroe offered early promise, but the campaign came to an end in the following round with a 0–2 loss at Cherry Tree.

Though the season brought mixed results on the pitch, Accrington’s increasing exposure to the Scottish game and its players marked a clear shift in strategy—laying the groundwork for stronger squads in seasons to come.

1886–88: Financial Strains, Formidable Form, and a Final Without a Rival

The 1886/87 season opened not with optimism, but with friction between Accrington FC and their landlords, the Cricket Club. The cricketers were demanding payments for the use of spectator stands, despite the Football Club still owing £80 from the original construction of the seated grandstand. The financial reality of running a professional club was beginning to bite. Fundraising efforts were launched to bridge the gap—most notably through raffles, including one with an extraordinary first prize: a house.

On the pitch, the season brought mixed results. In the FA Cup, Accrington travelled north to face Scottish side Renton, narrowly losing 0–1 in a closely contested match. In the Lancashire Cup, the club pulled off a surprise 2–1 victory over local rivals Darwen, followed by a commanding 6–1 win against Higher Walton in the second round. However, they were forced to withdraw before the third round tie with Witton could be played.

The 1887/88 season marked a turning point, with Accrington boasting one of the strongest squads in the North of England. The team’s dominance was reflected in emphatic victories: Glasgow Northern were beaten 4–1, Thornliebank thrashed 10–0, and even Wolverhampton Wanderers—albeit their reserve side—were dispatched by the same scoreline. Bolton Wanderers fell 3–1 in another impressive display.

The FA Cup campaign began with a stunning 11–0 demolition of Rossendale, followed by a 3–2 victory over Burnley in the second round. The third round proved a step too far as Blackburn Rovers overcame Accrington 3–1.

In the Lancashire Cup, Accrington were even more ruthless. A staggering 20–1 win over Lower Darwen was followed by solid 4–0 victories over both Higher Walton and Darwen. In the semi-final, Accrington drew 1–1 with Witton at The Copse, Fleetwood. The replay at Blackburn’s Leamington Street saw Accrington win 2–1, with Conway’s controversial goal at the heart of Witton’s protest. They claimed the goal was offside and that both the umpires and referee had misunderstood the rules. A formal hearing—with diagrams provided—proved the officials correct, and the appeal was dismissed.

Accrington advanced to a highly anticipated final against Preston North End—but what followed was one of the most bizarre chapters in Lancashire Cup history. The Lancashire FA chose Leamington Street, home of Blackburn Rovers, as the final’s venue. However, Preston officials flatly refused to play there, citing previous hostile treatment from Blackburn spectators. A stalemate ensued. The FA, determined not to appear weak in the face of club pressure, refused to relocate the fixture and continued to advertise the match at Blackburn.

On the day of the final, Preston North End did not appear. In their absence, Accrington kicked off, scored a token goal against an empty half of the pitch, and were declared Lancashire Cup winners by default. Though anticlimactic, the Lancashire FA had prepared for such an eventuality: they had paid losing semi-finalists Witton £10 to remain available as emergency opponents. The stand-in match proceeded before a modest crowd of 2,000. Perhaps with their motivation drained, Accrington were humbled 4–0 by Witton in an ironic coda to their championship.

Despite the farcical ending, Accrington’s official claim to the Lancashire Cup stood, and the season firmly established their position as one of the North’s most formidable clubs—both admired and, increasingly, controversial.

1888: The Birth of the Football League and Accrington’s Place Among the Founders

By 1888, it had become increasingly clear among the professional clubs of Northern England that a new structure was needed to sustain public interest in the game. While cup competitions remained popular with spectators, their limited number—and the chaotic nature of early-round exits, fixture changes, and multiple replays—left too many gaps in the calendar. For clubs and supporters alike, there was a growing desire for something more consistent and predictable.

The first steps toward change were taken at a meeting held on 23 March 1888 at Anderton’s Hotel in London, on the eve of the FA Cup Final. The discussions laid the groundwork for what would soon become the most significant development in English football. A second, decisive meeting followed on 17 April at the Royal Hotel in Manchester, where the new competition was formally established.

At the Manchester meeting, a name for the new body was debated. William McGregor of Aston Villa initially proposed “The Association Football Union,” but it was felt to resemble too closely the “Rugby Football Union,” potentially causing confusion. Instead, Major William Sudell of Preston North End suggested the simpler and more distinctive title—“The Football League”—which was swiftly and unanimously adopted.

Thus, the Football League was born, and the inaugural season kicked off in September 1888 with twelve founding members, all drawn from the Midlands and North of England. The pioneering clubs were:

Accrington, Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Burnley, Derby County, Everton, Notts County, Preston North End, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion, and Wolverhampton Wanderers.

Each club would play every other team twice—once at home, once away—creating a regular and balanced fixture list for the first time in the sport’s history. A points system was introduced, though not without debate. Initially, there was a proposal to award just one point for a win. However, shortly after the season commenced, the current system was adopted: two points for a win, one for a draw, and none for a loss.

This revolutionary structure brought much-needed order to the professional game, providing a platform that would endure and evolve over the decades to come. For Accrington, it marked their entry into a new era—standing shoulder to shoulder with the giants of the North as one of the original twelve members of the Football League.

Accrington’s 1888–89 Campaign: A Founding Season in the Football League

Accrington entered the inaugural 1888–89 Football League season with pride and optimism, one of the twelve pioneering clubs to take part in what was now the world’s first organised league competition. However, while they brought experience and a competitive squad, the challenges of maintaining consistency at the highest level soon became apparent.

Accrington’s first-ever League match took place on 8 September 1888, away to Everton at Anfield (then Everton’s home ground). The match ended in a 2–1 defeat for Accrington, despite a promising performance. The club’s first Football League victory came a week later, on 15 September, when they defeated Derby County 6–2 at Thornyholme Road—a resounding statement of their attacking potential.

The team quickly established a reputation for their physical style of play and unpredictable results. While capable of scoring freely at home, Accrington struggled for consistency, particularly away from Thornyholme Road. They recorded notable wins over Stoke (4–2), Notts County (3–1), and Blackburn Rovers (5–1), demonstrating their ability to compete with some of the more established names in the League.

However, defensive frailties and a lack of squad depth began to show as the season progressed. Accrington’s away form was especially poor, with just one win on the road all season. Still, their strong home performances helped them avoid the ignominy of finishing near the bottom of the table.

By the close of the campaign, Accrington had played all 22 fixtures, finishing with a record of:

- 6 wins

- 8 draws

- 8 defeats

They ended the season in seventh place, comfortably above Stoke and Notts County, who had to apply for re-election to the League. Preston North End, known as “The Invincibles,” dominated the season, going unbeaten and finishing as runaway champions.

Though Accrington were not among the frontrunners, their mid-table finish in such a prestigious and competitive league was a respectable achievement. The campaign highlighted both the club’s strengths—particularly their spirited home form—and the challenges they would need to address to remain competitive in the rapidly professionalising world of English football.

The 1888–89 season not only marked a milestone for the sport but also secured Accrington’s legacy as one of the founding members of the Football League—forever etched in football history.

Accrington in 1889–90: Consolidation in the Second Football League Season

Following a respectable seventh-place finish in the inaugural Football League campaign, Accrington approached the 1889–90 season with cautious ambition. The club retained much of its existing squad and continued to build on the momentum generated by their spirited home performances the previous year.

The Football League expanded in popularity and competitiveness in its second season, and while no new teams had yet joined, the quality and intensity of fixtures had increased across the board. For Accrington, consistency remained elusive, but their ability to compete with the League’s best remained evident—particularly on their home turf at Thornyholme Road, where the team remained a difficult opponent for any visitor.

Over the course of the 22-game season, Accrington once again displayed flashes of brilliance. One of the most notable results came on 23 November 1889, when they held the reigning champions Preston North End to a 1–1 draw, ending Preston’s 23-game unbeaten league run that had stretched back to the previous season. It was a spirited and disciplined performance that demonstrated Accrington’s tactical growth and their ability to frustrate even the strongest sides in the division.

Accrington also recorded a particularly emphatic 6–1 home victory over Stoke, as well as a 4–1 win over Derby County, reinforcing their status as one of the league’s most unpredictable and exciting attacking sides.

However, away form again proved to be their Achilles’ heel. A string of losses on the road, including heavy defeats to Blackburn Rovers (0–5) and Everton (1–5), stymied any hopes of a finish in the top half. Defensive vulnerabilities remained an issue, as the team struggled to keep clean sheets and often found themselves chasing games after early concessions.

Despite these challenges, Accrington managed to slightly improve on their previous league position. They ended the season in sixth place, with a record of:

- 9 wins

- 2 draws

- 11 defeats

They scored 48 goals and conceded 56, reflecting their status as a side that played adventurous, attacking football—often at the expense of defensive solidity.

The FA Cup, meanwhile, offered no respite. Accrington were eliminated in the First Round, falling 1–0 away at West Bromwich Albion, who would go on to reach the final.

Off the pitch, financial pressures remained a concern. Like many of the smaller Football League clubs, Accrington struggled to match the resources of larger urban sides such as Everton and Aston Villa. Gate receipts were modest, and tensions with the cricket club over facilities persisted, complicating long-term planning and infrastructure investment.

Nevertheless, the 1889–90 season marked another solid year for the club. Accrington had confirmed their place in the Football League as more than just founding members—they were competitive, combative, and capable of challenging any opponent on their day. But the storm clouds of financial strain and the growing divide between the League’s largest and smallest clubs were beginning to gather.

Accrington in 1890–91: Storm Clouds Gather

The 1890–91 season marked Accrington’s third campaign in the Football League and one that would expose the club’s growing limitations, both on and off the field. After two mid-table finishes, there had been hopes that the club could push on, but instead, the season revealed a team struggling to keep pace with the rapidly improving standards of the professional game.

A Faltering Start

From the outset, Accrington’s campaign was riddled with inconsistency. While the team retained a handful of experienced and capable players, there was a noticeable lack of depth in quality compared to the likes of Preston North End, Everton, or Aston Villa—clubs with stronger financial backing and larger crowds.

Accrington started the season with some promise, including a solid 2–2 draw at home to West Bromwich Albion and a morale-boosting 3–0 victory over Derby County, but these highs were few and far between. As the season progressed, defeats mounted, and confidence waned.

Crushing Defeats and Defensive Woes

One of the season’s low points came on 20 December 1890, when Accrington suffered a 0–8 defeat away to Derby County—still one of the heaviest losses in the club’s League history. That result typified a broader problem: while the team could occasionally threaten going forward, their defence was alarmingly porous.

Over the course of the season, Accrington conceded 63 goals—the joint-worst defensive record in the division, alongside Notts County. Their inability to shut down games meant that even strong performances often ended in disappointment. Close contests turned to defeats, and the club slipped further down the table.

The League Table Tells the Tale

By the end of the 22-game season, Accrington’s record stood at:

- 6 wins

- 4 draws

- 12 defeats

They scored 48 goals but, crucially, conceded 63, finishing in 10th place out of 12, narrowly avoiding the dreaded bottom two.

The bottom two teams—Stoke and Burnley—were forced into test matches (early promotion/relegation play-offs) against the best teams from the Football Alliance, which had become a significant rival to the Football League by now. Accrington’s narrow escape from this new pressure only masked the deeper structural issues beginning to surface within the club.

Cup Frustrations Continue

The FA Cup again offered little respite. Accrington exited early, falling in the First Round to Sunderland, a rising powerhouse from the North East who would soon become one of the top clubs in England. The loss underlined just how far Accrington had fallen behind the game’s emerging elite.

Growing Financial Pressures

Behind the scenes, the situation was becoming increasingly dire. Attendance figures were dwindling, with only the visits of major clubs like Aston Villa and Blackburn drawing respectable gates. The club’s ongoing dispute with the Cricket Club over the shared use of Thornyholme Road continued to be a source of friction, and there was little money available for strengthening the squad.

In contrast, other Football League clubs were becoming better organized and better funded. The professional era was taking shape at speed, and Accrington—once a pioneer—was being left behind.

A Season of Survival, but Only Just

The 1890–91 season was, in many ways, a season of survival for Accrington. The club had avoided finishing in the bottom two, but only marginally so, and the writing was on the wall. While still clinging to their Football League status, the gap between them and the leading clubs was widening fast—on the pitch, in the bank accounts, and in the grandstands.

It would prove to be a critical moment in the club’s history, setting the stage for an even more tumultuous 1891–92 season, when the club’s very future in top-flight football would come under threat.

1891–92: A Season of Stagnation

The 1891–92 season marked Accrington’s fourth year in the Football League and a continuation of the steady decline that had begun after their mid-table finishes in the League’s early years. Although the club avoided relegation, the campaign underlined their growing struggle to keep pace with the shifting landscape of English football.

A Faltering Start

From the outset, Accrington found wins hard to come by. Early-season fixtures included heavy defeats to more established sides, and though there were flashes of resilience, consistency proved elusive. Defensive lapses remained a defining feature, and the side often found itself chasing games rather than controlling them.

Despite a modest goal return from key forwards, including James Bonar and John Stevenson, the team lacked a cutting edge in decisive moments. Over the course of the 26-game season, they scored 50 goals but conceded 63 — the second-worst defensive record in the division.

Their final record read:

P26 – W6 – D5 – L15 – F50 – A63 – Pts17

This left them 11th out of 14 clubs, just three points clear of the test match places.

Defensive Struggles and a Leaky Back Line

Accrington’s defence was frequently overrun by more clinical opponents. Heavy defeats included a 5–1 loss away to Sunderland — the eventual champions — and a 4–0 reverse at home to Wolverhampton Wanderers. Clean sheets were rare, and even in matches where the forwards performed well, the back line often gave away leads.

Goalkeeper Joe Hay and full-backs John Stevenson and Thomas McLachlan worked tirelessly, but the unit as a whole lacked cohesion. Injuries and a lack of depth further hampered selection consistency.

Moments of Promise

There were, however, occasional bright spots. A 6–2 home win over Darwen in November offered a glimpse of the team’s attacking potential, while a spirited 2–2 draw against Aston Villa — one of the division’s strongest sides — in March provided a measure of encouragement. James Bonar finished the season as one of the club’s top scorers, and local support remained passionate, if increasingly frustrated.

Accrington’s six victories included wins over Notts County, Stoke, and West Bromwich Albion, but these were interspersed with long winless stretches that saw the club sink steadily down the table.

Off the Field: Finances and Friction

Away from the pitch, problems continued to mount. Gate receipts at Thornyholme Road declined as results worsened, and the club faced ongoing difficulties in raising funds to meet the growing demands of professionalism. Wages, travel costs, and facilities placed an increasing burden on the club’s limited finances.

The long-standing lease dispute with the Accrington Cricket Club — owners of Thornyholme Road — remained unresolved and cast further uncertainty over the club’s future. The team’s inability to expand or invest in infrastructure placed them at a growing disadvantage compared to better-resourced rivals.

A Club Falling Behind

As the professional game matured, clubs like Everton, Aston Villa, and Sunderland began operating on a scale Accrington could not hope to match. These sides boasted large followings, deep squads, and burgeoning reputations, while Accrington continued to rely on a patchwork of part-time players, gate money, and goodwill.

Though they avoided the bottom two and the test match required of them the following season, the writing was on the wall. Without structural change or significant investment, Accrington’s position in the First Division was growing increasingly untenable.

Looking Ahead

Despite the season’s struggles, Accrington lived to fight another day in the Football League — a small victory in itself. But the sport was changing fast. With the Football Alliance set to merge with the League and a Second Division on the horizon, the club would soon face a far more daunting challenge: not just survival on the pitch, but a fundamental decision about its place in the national game.

1892–93: The End of the Line

The 1892–93 season proved to be Accrington’s last in the Football League — a hard-fought but ultimately doomed campaign in which the club could no longer keep pace with the accelerating professionalism and growing financial demands of the national game.

A Familiar Struggle

After narrowly avoiding the bottom two the previous season, Accrington approached the new campaign with cautious optimism. But from the outset, it became clear that the side lacked the strength and consistency to compete effectively.

The defensive frailties of past seasons persisted. Accrington shipped 63 goals over 30 league games — among the worst records in the division — and although they scored a respectable 58, it wasn’t enough to win matches with any regularity.

The team suffered 17 defeats, and their record of 6 wins, 7 draws, and 17 losses left them in 15th place, second from bottom in the newly expanded 16-team First Division.

Crowds Dwindle, Debts Mount

Off the pitch, the situation was no less precarious. Attendances at Thornyholme Road continued to fall, with local support waning as results deteriorated. The club simply could not generate enough gate money to pay players or settle debts, and the long-standing tension with the Cricket Club — still their landlords — remained unresolved.

Accrington’s inability to invest in players of genuine top-flight quality became painfully clear. Rivals like Preston, Everton and Aston Villa were becoming highly professionalised operations, attracting crowds in the tens of thousands and luring some of the best talent in Britain. Accrington, in contrast, struggled to fill its ground and often relied on raffles and subscriptions to survive.

The End: Relegation and Resignation

At the end of the season, Accrington’s 15th-place finish meant they were required to defend their League status via a “test match” — the forerunner of modern relegation play-offs. Their opponents were Sheffield United, a rising club from the now-defunct Football Alliance, which had been absorbed into the League to form the new Second Division.

The match took place at Trent Bridge, Nottingham, on 22 April 1893, and was played before a sparse crowd. Accrington lost 1–0, condemning them to relegation to the Second Division for the following season.

Rather than take their place in the lower tier, Accrington made a dramatic and final decision:

They resigned from the Football League.

The reasons were both financial and philosophical. The club felt it could not sustain the costs of travel and professional wages without the guarantee of large gates that First Division fixtures brought. Competing at a lower level offered little appeal, and the club opted to return to regional football, joining the Lancashire League.

A Respected Farewell

Though the resignation marked the end of Accrington’s time in the Football League, the club departed with a measure of dignity. Of the League’s twelve original founding members, Accrington were the first to leave — not through bankruptcy or expulsion, but by choice.

Their departure was mourned by some in the footballing world as the loss of one of the game’s pioneers. Though modest in size and budget, Accrington had helped lay the foundations of league football in England and had for five seasons competed against the country’s finest.

Legacy of the League Years

From 1888 to 1893, Accrington played 132 Football League matches, recording:

- 39 wins

- 27 draws

- 66 losses

Though they never challenged for the title, their presence in the League’s formative years helped shape what would become the world’s most watched and admired football competition.

Their resignation did not mark the end of the club — but it was the beginning of a long decline that would, within three years, see the original Accrington Football Club fold entirely in 1896.

Yet their story is remembered as one of courage, community, and contribution. Accrington may have stepped away from the national stage, but their role as a Football League founder is etched permanently into the annals of the game.

1893–96: The Final Years in the Lancashire League

Following their exit from the Football League, Accrington F.C. joined the Lancashire League — a highly competitive regional competition established in 1889 that became a haven for ambitious clubs outside the national divisions.

Though no longer rubbing shoulders with giants like Preston North End and Aston Villa, Accrington still enjoyed a degree of local prestige and retained a loyal core of supporters. However, the realities of their financial situation — and the general evolution of the professional game — soon became impossible to ignore.

1893–94: A Step Down, But Still Respected

In their first season in the Lancashire League, Accrington remained a respected side. Fixtures included matches against emerging northern clubs such as Bury, Stockport County, Southport Central, and Fleetwood Rangers. The competition was fierce, and while results were mixed, Accrington often held their own — especially in home fixtures at Thornyholme Road, where local rivalries brought out larger crowds.

Yet even at this level, the financial strain was clear. Without the income of top-tier gate receipts, and with player wages still necessary to field a competitive side, the club was increasingly reliant on fundraisers, subscriptions, and benefactors.

1894–95: Slipping Further Behind

By the 1894–95 season, cracks began to show. Key players left for more stable clubs, while the club’s ability to attract talent diminished. Younger, fitter and better-funded clubs began to dominate the Lancashire League, and Accrington’s name carried less weight than it once had.

Attendances dipped further, and performances on the pitch faltered. Though still occasionally capable of inspired performances, consistency was lacking, and the club began to slide toward the lower half of the table.

1895–96: The Final Blow

The 1895–96 season proved to be Accrington F.C.’s swan song. Fielding an understrength and largely local team, they finished the season near the bottom of the Lancashire League and faced the very real threat of collapse.

Unable to recover financially, and with no viable path back to competitive or financial stability, the club made the inevitable decision. In 1896, after 18 years of existence, Accrington Football Club formally disbanded.

No public ceremony marked the end, no farewell fixture was played. The club that had stood proudly among the twelve founders of the Football League simply ceased operations — its name fading from fixture lists, match reports and local papers.

Legacy and Memory

The demise of Accrington F.C. left a vacuum in the town. It would not be until 1891, ironically while the original club was still limping through the League, that Accrington Stanley was founded—a separate club entirely, though its name would eventually become synonymous with football in the town.

The original Accrington, however, holds a unique and permanent place in football history.

- One of the twelve founding members of the Football League.

- Winners of the Lancashire Senior Cup in 1881 and 1888.

- A club that, while modest in stature, stood at the very heart of the game’s transition from amateur pastime to professional sport.

Though it disappeared before the turn of the century, Accrington F.C. helped shape the early decades of organised football in England—and laid a foundation that generations of clubs, players and fans continue to build upon.

Accrington F.C. – Timeline of Key Milestones

1878

- Club founded, likely under the name Accrington F.C. (not to be confused with Accrington Stanley, founded later).

- Played first friendlies and built a reputation as one of the stronger local clubs.

1879–80

- Entered the Lancashire Cup for the first time; reached the Semi-Final, losing to Blackburn Rovers.

1880–81

- Won the Lancashire Cup, beating Blackburn Park Road 6–4 in front of 4,000 spectators.

1881–84

- Continued to progress in both FA Cup and Lancashire Cup.

- Reached multiple finals; defeated Blackburn Rovers in the 1882–83 Lancashire Cup Final.

1884

- Expelled by the FA for illegal payments to players; became one of the central clubs in the professionalism debate.

- Alongside other rebel clubs, helped pressure the FA to legalise professionalism in July 1885.

1888

- Became one of the 12 founding members of The Football League, the world’s first organised football league.

1888–89

- Finished 7th in the inaugural Football League season—comfortably mid-table.

1889–91

- Experienced steady decline, finishing 6th in 1889–90, and dropping to 10th in 1890–91.

1891–92

- Finished 11th out of 14; narrowly avoided relegation by winning a test match against Sheffield United.

1892–93

- Finished 15th out of 16 in the new First Division.

- Lost their test match to Sheffield United and, facing re-election, chose to resign from the League rather than drop into the new Second Division.

1893–96

- Joined the Lancashire League, but financial hardship, loss of players, and declining crowds led to:

- Deteriorating results

- Mounting debts

- Disbandment in 1896

The 12 Founding Members of the Football League: What Became of Them?

| Club | Founded | Status Today | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accrington | 1878 | Dissolved 1896 | Only founding member to disband permanently |

| Aston Villa | 1874 | Active | Long-time top-tier club, now in the Premier League |

| Blackburn Rovers | 1875 | Active | Founding club, won early FA Cups, currently in the Championship |

| Bolton Wanderers | 1874 | Active | Historically significant; now in EFL League One |

| Burnley | 1882 | Active | Twice First Division champions; currently in the Championship |

| Derby County | 1884 | Active | Founding member, now in EFL League One |

| Everton | 1878 | Active | Longest continuous top-flight run; Premier League club |

| Notts County | 1862 | Active | Oldest professional club; currently in League Two |

| Preston North End | 1880 | Active | Won first League season unbeaten (“Invincibles”) |

| Stoke (now Stoke City) | 1863 | Active | Relegated from Premier League in 2018; now in Championship |

| West Bromwich Albion | 1878 | Active | Yo-yo club; alternates between Premier League and Championship |

| Wolverhampton Wanderers | 1877 | Active | Regular top-tier team; Premier League as of recent seasons |

Final Notes on Legacy

- Accrington F.C. is remembered for its bold stance on professionalism and helping force the FA’s hand on reform.

- Despite their relatively short lifespan (1878–1896), their involvement in forming the League cemented their place in footballing history.

- Their spirit arguably lived on in Accrington Stanley, who would eventually gain national recognition—though they were a separate entity.